1.1 Europe on the Eve of Expansion

Europe on the Eve of Expansion: Understanding the Roots of the United States

The United States, as a nation, is a product of European cultural and historical developments. To comprehend the origins of the United States, it is essential to explore key events in Western history, particularly European History, that predate the founding of the U.S. in some cases by centuries.

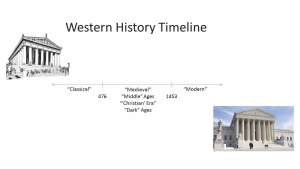

Western History Timeline

Western history can be categorized into three distinct periods:

Classical Era (until 476 CE): This era encompasses the civilizations of the Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians. The year 476 CE, marked by the sack of Rome, serves as a symbolic end of the Classical period, though this demarcation is somewhat arbitrary. Medieval Period (476 - 1453 CE): The Medieval period, also known as the Middle Ages, the Christian Era, or the Dark Ages, begins with the decline of the Roman Empire. This era is characterized by the prominent role of the Roman Church in governance and culture, transitioning from a celebration of earthly life to a focus on spirituality and the afterlife. Modern Period (Post-1500 CE): Contrary to the common perception of 'modern' referring to contemporary times, the academic definition places the start of the Modern period around 1500 CE. This period is marked by significant shifts in thought, leading to the Renaissance and the Reformation.

Key Concepts in Medieval Society: The Three Estates

Medieval European society was intricately organized into three distinct but interdependent 'estates', each playing a crucial role in maintaining the societal structure:

Bellatores (Nobility and Warriors): This estate comprised the nobility and warriors, whose primary responsibility was the protection and defense of the realm. Their role was not only martial but also included the governance and administration of lands. They were the protectors of both the clergy and the peasants, ensuring the security and stability necessary for the functioning of society. Oratores (Clergy): The clergy were entrusted with spiritual matters and the salvation of souls. This estate was crucial for maintaining the religious and moral fabric of society. The clergy provided guidance and support to the other estates, offering spiritual services and moral leadership. They played a mediating role between God and the people, and their influence extended into education and learning. Obradores (Peasants and Workers): Constituting the majority of the population, this estate was responsible for agricultural and physical labor. The peasants and workers produced the food and goods necessary for the survival and well-being of society. Their hard work supported both the bellatores and oratores, enabling the nobility and clergy to fulfill their respective duties.

Interrelationship of the Estates

The three estates were deeply interconnected, each relying on the others for survival and functioning. The nobility provided protection and governance, ensuring a stable environment where the clergy could focus on spiritual matters and the peasants could work the land. The clergy, in turn, offered spiritual guidance and moral support to both the nobility and peasants, legitimizing the social order and providing education. The peasants and workers sustained the entire structure through their labor, feeding and supporting the other two estates. This interdependence created a societal balance, where each estate had a defined role and contributed to the collective well-being and stability of medieval society.

This symbiotic relationship, while theoretically harmonious, often masked underlying tensions and inequities, which would eventually contribute to societal changes and challenges in the late medieval period.

The Renaissance: A Reevaluation of Medieval Order and the Role of the Church (Post-1453 CE)

The Renaissance, translating to 'rebirth' from French, was a period of fundamental transition from the medieval order, characterized by the resurgence of Classical knowledge and the arts. This period, commencing near the middle of the second millennium CE (1300s), was not just a revival of ancient aesthetics and intellectual pursuits; it catalyzed a profound reevaluation of the prevailing medieval societal structures and the role of the Church.

Revival of Classical Knowledge

The Renaissance marked the rediscovery of Greek and Roman texts, leading to a renewed interest in humanism, science, philosophy, and art. This revival directly challenged the medieval world's predominantly religious and theological focus, which had been underpinned by the Church’s authority. Classical texts offered alternative perspectives on human existence, ethics, and governance, diverging from the Church-dominated narratives of the Middle Ages.

Impact of the Fall of Constantinople

A pivotal event in the Renaissance was the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. This event led to the migration of Eastern scholars to Western Europe, carrying with them precious manuscripts and knowledge from the Byzantine Empire. This influx of Eastern scholars and their texts played a crucial role in rekindling interest in Classical learning and knowledge. The integration of this rich intellectual heritage into Western Europe was instrumental in fostering the Renaissance's intellectual revival and cultural flourishing.

Questioning the Medieval Order

As Renaissance thinkers delved into Classical texts, they began to question the rigid hierarchies and roles defined by the medieval societal structure. The previously unchallenged authority of the Church, which had extended its influence into every aspect of life, including politics, education, and morality, faced scrutiny. This intellectual awakening spurred debates on individualism, the role of the state, and the nature of human freedom.

Impact on the Church's Role

The rediscovery of Classical knowledge brought the practices and doctrines of the Church into question. Renaissance humanists, armed with insights from ancient texts, began to critique the Church’s teachings and its role in society. This critical examination laid the groundwork for the Reformation, where figures like Martin Luther and John Calvin would challenge the Church’s authority more directly, leading to profound religious and societal shifts.

Cultural and Artistic Flourishing

The Renaissance was also a period of extraordinary artistic expression, much of it supported by wealthy patrons who were often at odds with the Church’s views. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, inspired by Classical ideals, created works that emphasized human experience and naturalism, a stark contrast to the predominantly religious themes of medieval art. This focus on humanism and the empirical study of the natural world further encouraged a questioning of the medieval order and the Church’s teachings.

The Renaissance was a period of intellectual and cultural ferment that questioned and ultimately transformed the medieval societal order. The revival of Classical knowledge, fueled significantly by the migration of Eastern scholars following the Fall of Constantinople, did not just reintroduce ancient art and philosophy to Western Europe; it challenged the existing medieval paradigm, particularly the role and authority of the Church, setting the stage for the modern era.

The Reformation and Its Impact: Challenges, Reforms, and Consequences

The Reformation was marked by a series of challenges to the Catholic Church's authority, leading to religious and societal upheaval. While Martin Luther is often credited with initiating this movement, we should place him in a broader context including earlier reform efforts, Luther's specific proposals, the Church's inability to silence him, and the unintended consequences of the Reformation.

Precedents of Reform Attempts

Prior to Martin Luther, there were notable figures who attempted to reform the Church. One such figure was Jan Hus, a Bohemian priest who criticized Church practices like the sale of indulgences and advocated for a return to practices based on the Bible. However, Hus's movement failed primarily due to the Church's strong opposition, which culminated in his execution at the Council of Constance. His martyrdom highlighted the risks associated with challenging the Church's authority and doctrines at that time.

Martin Luther's Proposals for Reform

Martin Luther, a German monk and theologian, propelled the Reformation forward with specific criticisms and proposals. Central to his critique was the Church's practice of selling indulgences, which he viewed as a corruption of true Christian teachings. Luther proposed a return to the Scriptures as the sole source of religious authority, a concept known as 'sola scriptura.' He also emphasized salvation by faith alone ('sola fide'), challenging the Church's teaching on salvation through works and sacraments. His ideas were systematically laid out in his Ninety-Five Theses, which became a manifesto for reform.

Why the Church Could Not Silence Luther

Unlike earlier reformers, Luther benefited from several factors that the Church could not easily counteract. He had the protection of influential figures like Frederick III of Saxony, who provided him with a level of political immunity. Additionally, the advent of the printing press allowed Luther's ideas to spread rapidly and gain a widespread following, making it difficult for the Church to suppress his teachings.

Unintended Consequences: Peasant Rebellions

Luther's calls for reform inadvertently inspired peasant rebellions across Germany. These revolts were fueled by grievances against feudal oppression and economic hardships, with peasants drawing inspiration from Luther's emphasis on spiritual equality and freedom. Luther, however, did not support these rebellions, as his primary focus was on religious reform, not social revolution. The violent suppression of these uprisings demonstrated the complex interplay between religious and socio-economic factors during the Reformation.

John Calvin's Influence on the Reformation

John Calvin, a French theologian and reformer, emerged as a leading figure in the Reformation after Luther. Calvin's teachings and theological insights, particularly his emphasis on the sovereignty of God and predestination, further intensified the movement. He established a distinct branch of Protestantism, known as Calvinism, which advocated for a form of church governance that was more democratic than the hierarchical structure of the Catholic Church.

Calvinism and Democratic Church Governance

Calvin's model of church governance, often referred to as 'Presbyterian polity,' was groundbreaking. It involved a system where the church was governed by elected elders and ministers, reflecting a more democratic and participatory structure. This approach contrasted sharply with the top-down hierarchy of the Catholic Church and influenced the development of democratic principles in ecclesiastical settings. Calvin’s emphasis on community participation and accountability in church affairs laid the groundwork for broader democratic ideals in governance.

Calvin's Impact on Social and Political Thought

Calvin's influence extended beyond religious practices to social and political thought. He advocated for a society based on moral principles derived from the Bible, emphasizing the importance of a disciplined and virtuous life. Calvinism's stress on individual moral responsibility and ethical governance resonated with emerging democratic ideas and influenced political thought in Europe and beyond.

Influence on New England Settlers and U.S. History

The Calvinist doctrine significantly influenced the English Puritans, a group of Protestant reformers who sought to 'purify' the Church of England from its remaining Catholic practices. Many of these Puritans, holding Calvinist beliefs, migrated to New England in the early 17th century. Their Calvinist worldview shaped the development of the New England colonies and, subsequently, the social and political fabric of the United States. The emphasis on a covenant community, representative governance, and a work ethic aligned with democratic ideals were integral to the Puritan settlements and left a lasting imprint on American values and institutions.

The Church's Response: The Council of Trent

In response to the growing Protestant movement, the Catholic Church convened the Council of Trent (1545-1563), which marked the beginning of the Counter-Reformation. The Council reaffirmed core Catholic doctrines and addressed various abuses and issues raised by reformers. It clarified Catholic teachings, reformed clerical life, and established seminaries for the proper training of priests. While the Council did not reconcile Protestant and Catholic differences, it revitalized the Catholic Church and helped it respond more effectively to the challenges posed by the Reformation.

Summary

The Reformation was a complex and multi-faceted movement that reshaped European religious and societal landscapes. It began with earlier reform efforts, gained momentum with Martin Luther's critiques, and led to significant political and social changes, including the rise of Protestantism. The movement's unintended consequences, such as peasant rebellions, and the Catholic Church's concerted response at the Council of Trent, further illustrate the impact of the Reformation on European and eventually US history.

Consequences and Evolving Perspectives: The Reformation's Far-Reaching Impact

The Reformation had far-reaching consequences beyond the religious sphere. It led to a significant decline in the authority of the Church, contributed to the rise of the nation-state, increased literacy, and laid the groundwork for nationalism. Additionally, the religious conflicts it sparked were a catalyst for some European intellectuals to reassess the role of the Church in society leading to the Enlightenment.

Decline in Church Authority

The Reformation, initiated by figures like Martin Luther and John Calvin, directly challenged the central authority and practices of the Catholic Church. This movement, supported by the spread of printed materials critiquing the Church, eroded the Church's control over religious life and doctrine. The establishment of Protestant denominations decentralized religious authority, shifting power from a singular, unified Church to diverse, often localized, religious institutions.

Rise of the Nation-State

As the Reformation questioned the Church's authority, it inadvertently strengthened the power of secular rulers. Kings and princes, particularly in Northern Europe, began to assert more control over religious affairs within their territories, often aligning with Protestantism to consolidate their power. This shift played a crucial role in the development of the modern nation-state, where the central authority was vested in a sovereign nation rather than a universal church.

Increase in Literacy

The Reformation's emphasis on personal interpretation of the Scriptures necessitated and encouraged literacy among the general populace. The translation of the Bible into vernacular languages and the proliferation made possible by the printing press made religious and secular texts more accessible, leading to a significant increase in literacy rates. This rise in literacy was a key factor in the spread of Reformation ideas and facilitated greater public participation in religious and political discourse.

Foundations for Nationalism

The translation of religious texts into vernacular languages not only promoted literacy but also fostered a sense of shared identity and culture among speakers of the same language. This development, coupled with the increasing role of national leaders in religious matters, laid the foundations for modern nationalism, where people began to identify themselves more with their nation and language group than with a pan-European Christendom.

Religious Wars and Intellectual Reassessment

The religious fragmentation caused by the Reformation led to a series of devastating religious wars across Europe, most notably the Thirty Years' War. The brutality and destruction wrought by these conflicts led some European intellectuals to question not only the Church's role in governance but also the utility of religion itself. This skepticism contributed to the Enlightenment, where thinkers increasingly advocated for secularism, tolerance, and a separation of church and state.

Summary

The Reformation, while initially a religious movement, had profound and lasting impacts on the political, social, and intellectual landscape of Europe. It diminished the Church's authority, contributed to the rise of nation-states, increased literacy, fostered nationalism, and set the stage for the Enlightenment. These changes were instrumental in shaping the modern Western world, laying the foundations for the principles of democracy, secularism, and public discourse that characterize contemporary societies.